People have been coming to Jávea for thousands of years. Archaeological evidence found in a cave on the northern flanks of Cabo de San Antonio has been dated back to 30,000 years ago and are through to be the remains of a nomadic hunter-gatherer group that would have looked out from their shelter on to a landscape very different from today with the coastline several kilometres further out that it is now.

At the end of the Ice Age, around 10,000 years ago, sea levels rose, climates changed and the landscape evolved into something much like we see today. The fledgling human societies adapted to these changes, moving away from the shelter of natural cavities to develop small communities, some in the valley whilst others took advantage of hills and high places to develop defensive settlements. Agriculture and the keeping of livestock came to dominate their lives whilst the arrival of migrants from the Middle Eastern region saw significant technological advances such as the emergence of pottery and stone polishing.

The Iberian culture developed at the end of the 6th century BCE, the first great civilisation on the peninsula which extended from the southern lands right up to what is now southern France. They introduced the written language using their own alphabet and coins with which to trade. Evidence of an Iberian settlement was discovered not so long ago on La Plana de Justa right below the steep south-eastern face of the mountain of Montgó, although nothing much more than the remains of a few walls can be seen. Of more significance was the discovery of a collection of gold and silver jewellery by a workman in the Lluca zone in 1904, a collection that has become known as “El Tesoro Ibérico de Xàbia”. The original pieces are in Madrid but a replica of the collection can be seen in the municipal museum in the historic centre of town.

The Romans began arriving in the late 2nd century BCE and set about developing the agricultural potential of the valley, growing cereals, olives and grapes for the production of wine. But the clearest evidence of the Roman occupation lies on the coast in the Arenal zone where a great pool excavated out of the tosca stone, now known as the “Queen’s Baths”, was thought to have been part of the fish factory where salted fish and garum sauce was produced. Further along the coast are the deep narrow channels of “Séquia de la Nòria” which allowed seawater to flood to lowland beyond the coast where it evaporated to leave the salt used in the industry.

The Romans had departed the region by the 7th century CE and the area was largely uninhabited for some two centuries until the arrival of the Moors in the 9th century CE. Not much remains of their tenure over the land aside from evidence of agricultural irrigation networks which took advantage of the water wheel technology that was introduced by the incoming civilisation. However there are several sites around the Capsades and Lluca zones from which archaeologists have been able to build up a picture of the Islamic world that existed until the Christian reconquest in the mid-13th century CE.

Knights of Jaume I, King of Aragon, arrived in what is now called Dénia in 1244 and the lands of the valley of Xàbia were incorporated into the newly-formed Kingdom of Valencia. Christian settlers from Catalonia moved into the area and developed a settlement on the side of a hill on which they built a square walled enclosure to protect themselves against the increasing danger from Saracen and North African raiders.

The settlement saw significant growth during the late 15th and 16th centuries and in 1513 the architect Dominic Urteaga was commissioned to build the church-fortress of San Bartolomé, expanding what had until then been a simple but effective square tower. High defensive walls more than a metre thick were built around the expanded nucleus, now long destroyed but their route can still be traced today in the unique angular shape of the historic centre. Three main gates controlled access to the village: Portal del Clot to the south, Portal de la Ferrería to the west and Portal de la Mar to the east. A fourth, Portal Nou, was added in the 19th century to provide a northern access point.

In July 1612, Xàbia was granted the title of “Villa Real” – “Royal Town” – which permitted the formation of a separate municipal government after years of control by the city of Dénia. In 2012 the town celebrated the 400th anniversary of this royal decree with a special ceremony and ringing of the church bells.

The victory of the Boubons in the War of Spanish Succession (1705-1714), the faction supported by Xàbia, saw the town received several privileges from the Crown, including concessions to export fruit and other goods such as wheat and raisins through its port and the use of the heraldic isis and two crowned L’s on its coat of arms as a reward for the town’s loyalty to Felipe V. Interestingly Dénia supported the other side, the Austrian-Hapsburg claim, not the first time that he two municipalities would lend its weight to opposite forces.

In the early 19th century, despite the peninsular falling into the hands of Napoleon, the raisin industry boomed in the Marina Alta region, bringing Xàbia untold wealth which would define its development during the time. England and North America were the primary export destinations and at its peak some 33,000 metric tons of raisin passed through the port. At the beginning of the 20th century the industry was rocked by the spread of grape phylloxera and by competition from Greece, Turkey, the United States and Australia. War and politics also played a part in its demise durng the last century so that by the 1970s it had become more of a symbolic activity, a determination to keep alive the traditions.

During the industry’s peak, the town’s huge mansions were raised such as the Casa dels Bolufer, Casa de les Primícies, Casa Arnauda, Casa Abadía and Casa de Tena, all of which retain their dominance in the 21st century. Many of them had tall towers, none of which could be higher than the belltower of the church, from which the rich landowners could watch as their produce was transported to the port to be transported across northern Europe and beyond. The town walls were demolished to accommodate the town’s expansion and wide avenues, now known as Avenida d’Alacant and Avenida Principe d’Asturis were built to ease the transport of goods to the port from Placeta del Convent, the avenues lined with more elegant houses.

The town was ravaged during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). The ancient church still bears the scars on its outer walls whilst inside the huge wooden carved altarpiece that dominated the apse was set ablaze and destroyed and many decorative items looted. The catacombs below remain choked with debris that was swept into a giant hole after the war had ended, debris that rumours insist included an unexploded shell. The 17th century Convento de los Mínimos in Placeta del Convent was destroyed as was the convent building next to the church which was rebuilt to become the municipal indoor market.

The British have always had a strong presence in Spain, either as engineers in the mines of Asturias and Andalusia or as soldiers with Wellington’s Peninsular Army. Indeed, the narrow guage railway that ran from Alicante to Dénia was built by British engineers to serve the quarries and transport the various fruit grown in the region to ports to be shipped abroad.

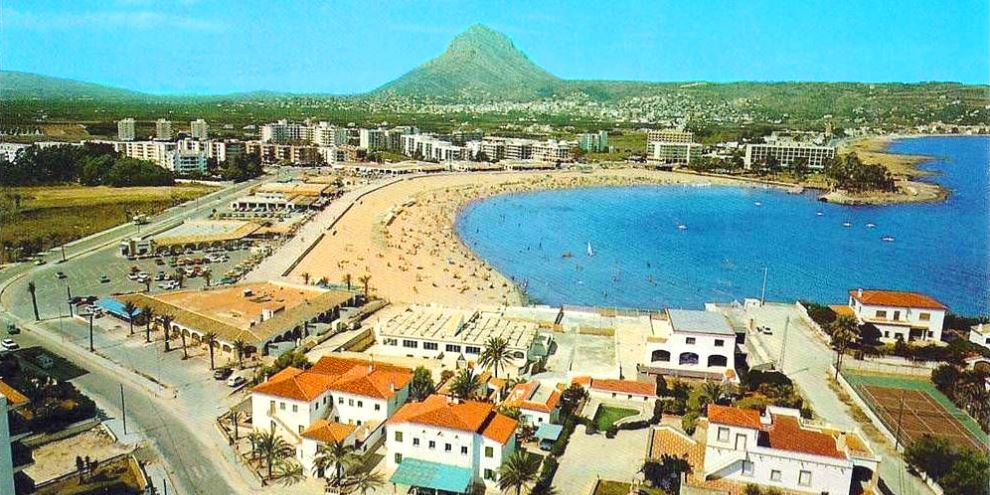

Package tours began in the late 1950s and Jávea was soon to build on their popularity – but with restraint. Seeing the villages of Benidorm and Calpe dominated by high rise apartment blocks and hotels, a local by-law was put in place that prevented – and still does prevent – buildings of more than four storeys from being built in the town. There are still a couple of examples of high-rise accommodation that managed to be built before the restrictions, one in the port and one in the Arenal, both overlooking the beaches.

In the past three decades the town of Jávea has seen incredible growth as it built on its popularity as a tourist destination. Infrastructure has been improved, services modernised and the town currently welcomes thousands of visitors from across Europe every summer. Its population has grown markedly as well from around 11,000 in the 80s to a peak of some 34,000 of which some 50% for foreign residents although it has dropped recently to 27,604 (2019).

Jávea rode the “La Crisis” fairly successfully. Visitor numbers rose, unemployment fell and sustainable development was promoted to safeguard its future. The COVID-19 crisis of 2020 dropped a sizeable spanner in the works but the town’s leaders reacted quickly with social and economic recovery plans worth some 6 million euros, some of the best in the region, to put the town on a firm footing to emerge relatively unscathed.

“The water, the light, the wind, the small corners of Xàbia have always led me by the hand towards an inner growth in which I cannot ignore those people who, since my childhood, taught me to share, next to the boats , in that warm corner of the Granadella, the illusion, the simplicity, the music. “

ENCARNA MARTÍNEZ OLIVERAS