Researched and written by Mike Smith – November 2025

The sea tells its stories not in words, but in the shape of the shore and the rhythm of the tides. In Xàbia, those stories unfold like a stubborn, winding chronicle carved into the coastline. Our particular story begins with a horseshoe-shaped inlet the Romans once called a harbour, centuries before cartographers etched its outline onto parchment. This natural cleft, later known as Caleta del Racó, offered refuge to ancient mariners and fishermen, a cradle of calm in a restless sea.

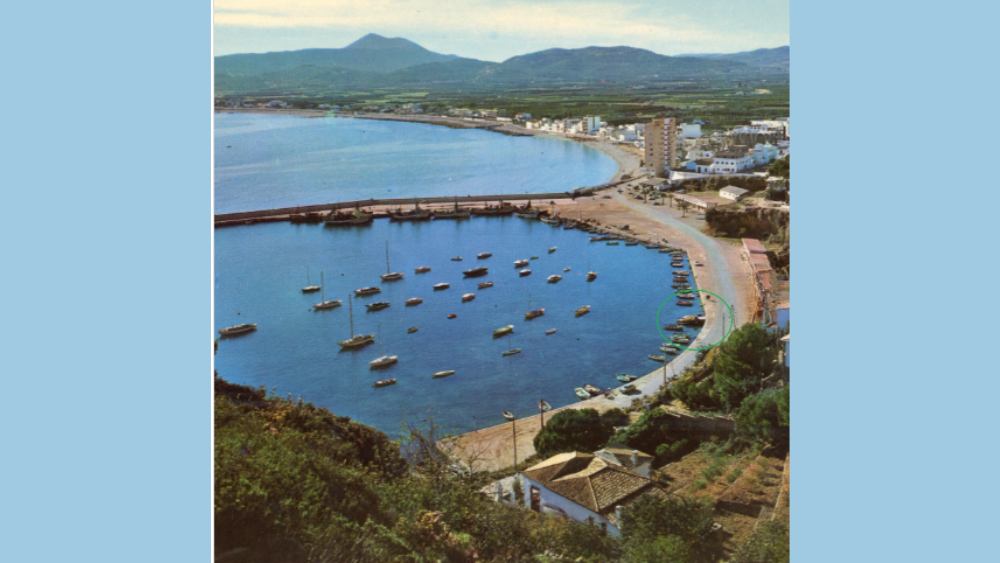

Though the cove itself has long vanished beneath layers of progress and concrete, its gentle curve still whispers through the landscape, just barely visible behind the parking area near the harbour entrance. Its memory also survives in the name of the road that skirts the top of the steep slope once tumbling into turquoise waters: Carrer La Caleta.

This is the story of how a modest cove grew into the bustling modern harbour of Port de Xàbia. Of how an artillery tower once stood sentinel over its waters. Of how the golden age of the raisin trade spurred its expansion. And of how modernisation, in its relentless tide, has nearly swept away the traces of its past.

Nearly two thousand years ago, fishing skiffs and cargo-laden boats sought shelter in this inlet, protected to the north by the rugged headland now known as Cap de San Antonio. Inland, the fertile plains flourished with vineyards, olive trees and wheat, sustaining a thriving local economy. Roman settlers established rural estates that produced wine, olive oil, and grain, commodities that would travel far beyond these shores.

From this quiet cove, amphorae filled with local wine were loaded onto ships and dispatched across the Roman Mediterranean, linking Xàbia to distant provinces along the Iberian coast and toward Rome itself. Recent archaeological investigations have even uncovered the remains of a Roman villa nearby, a silent witness to the region’s ancient role in trade, agriculture, and maritime life.

Time layered itself like sediment. Empires rose and crumbled; the Roman world, once so certain, fractured and fell. The Visigoths swept down from the north, establishing footholds in the valleys and hills. Later, invaders from North Africa arrived from the south, bringing new faith, new customs, and their own imprint on the land. Through it all, the small cove did what coves have always done – receive, protect, bear silent witness.

By the 11th and 12th centuries, chronicles of the time speak of a port named Tartán, nestled beside a mosque. These aren’t just dry entries in medieval ledgers, they are living proof that this was a place not only of arrival but also of devotion, of trade and transition. Here, on a narrow seam of land and sea, ordinary lives unfolded: fishermen unloading their catch, merchants exchanging goods, travellers offering prayers before setting sail again. The cove remained constant, a quiet stage for centuries of human rhythm.

Then, in the early 13th century, the Christians of Aragón came, part of the great Reconquista that reshaped the Iberian Peninsula. With them came new laws, new faith, and the first written reference to a village called “Yxabee,” nestled within the jurisdiction of “Denje” (Dénia), established on a small rise about 1.5 kilometres inland. It was a modest settlement, but it marked the beginning of a new era, one that would eventually reach the shoreline and fortify it.

By the late 16th century, the strategic value of the small cove had hardened into stone and mortar. A fortress rose above the landing in 1578: the Torre de Sant Jordi, also called Torre de la Mesquida, for the ruins of the mosque lay beneath its foundations. The tower was hexagonal, a modern artillery watchtower built to guard anchored ships and menace would-be raiders, especially the Barbary corsairs who prowled these waters in search of plunder, slaves, and footholds.

The tower’s life as a sentinel was finite. When the threat receded, its stones began to tell other stories: neglect, decay, reinvention. Ruins gave way to a modern high-rise apartment block – Torre del Puerto – while some of its cannons found new life around the historic church in the old quarter, echoes of a military past now folded into civic memory.

The 19th century reimagined the coast again. Stones from the tower as well as from the defensive walls that were being dismantled at the time became the foundations of a new fishing harbour which was finished in 1879, built during an era when Xàbia’s economy swelled with the succulent riches of raisins. La Sultana, Xàbia’s raisin brand, had earned a reputation across Europe and North America, and the port, with its customs and naval services, cemented the town’s role in that trade. Prosperity, however, is thinly veneered on shifting global currents. Political and economic storms in the early 20th century, changing routes and ferocious competition abroad, felled the raisin industry. However, the town did not vanish; it pivoted. Fishing, once again, became the mainstay that steadied families through unpredictability.

Despite the emergence of a larger harbour area, Caleta del Racó itself retained a softer life: a shingle beach for shellfish gathering, a place to beach small boats, and a place for a first swimming lesson for children. However, in the 1920s, a decision to expand the harbour further threatened the existence of the popular cove. Work on an eastern breakwater began in earnest by 1933 but was interrupted by the civil war in 1936 and the harbour took on a more militaristic role. In 1938 a cut into the hillside behind the cove produced a sealed structure whose meaning would be debated for decades. Long hidden under undergrowth after the war, it was rediscovered only in 2016. First thought to be an air-raid shelter, later study suggests it served as an ammunition depot for Republican torpedo and anti-submarine boats. Unsafe to visit in person, the site now opens to the curious only through the town hall’s digital doorway, a virtual window onto an object that resisted being tamed by time.

Once the guns fell silent and the nation began rebuilding, the harbour works resumed. Between 1947 and 1957 the eastern breakwater was pushed farther, a western counterpart completed, and the port grew under the gaze of townsfolk who came to watch the engineering spectacle. Explosives removed cliff-face to make room; the same alterations later made the headland vulnerable, collapsing under stormed seas and blocking access in 2008 before reinforced concrete returned a semblance of stability. The Caleta’s original curve was eventually buried, sand and stone filled the hollow, a new platform laid where a cove had been; it is now a car-park and a storage area. But, even as its outline can still be traced, change is afoot: approved plans now envisage a three-storey car park for 123 cars and a plaza with a rooftop viewpoint. The last remaining evidence of this ancient and popular cove will be buried forever.

The disappearance of the cove is not without precedent. Another beloved landmark in the port once stood proud before vanishing beneath the weight of progress, a jutting red rock known affectionately as La Penyeta Roja. It was more than stone; it was a gathering place, a sun-warmed perch for swimmers, and a launch point for llaüts, the traditional wooden boats that once bobbed gently in the harbour’s embrace.

As the port expanded and the road pushed forward, La Penyeta Roja was swallowed by asphalt and concrete. But memory has a way of resisting erasure. A local fiesta peña still bears its name, and each late summer, during the Mare de Déu de Loreto festivities, its legacy resurfaces in the form of bright, cheerful t-shirts, a fleeting but vivid reminder of the rock that once anchored so many seaside moments.

By the early 1970s, the harbour of Xàbia had settled into a shape that would feel familiar to modern eyes. The age of raisins and merchant schooners had passed; in its place, a new rhythm took hold, one defined by the tides and the daily return of fishing boats. At the heart of this transformation stood La Lonja, the fish market, which quickly became the port’s beating heart. Here, local fishermen hauled in their catch and laid it out for sale, destined for the kitchens of nearby restaurants or packed off to markets farther afield.

In 1977, as the fishing industry matured, plans were drawn up to give La Lonja a more permanent and purposeful form. Those blueprints finally came to life in 1995 with a major reconstruction that modernised the facility without stripping it of its soul. The new design brought upgraded auction halls, better hygiene standards, and improved access for both fishermen and buyers, ensuring that tradition and efficiency could coexist under one roof.

Today, La Lonja remains a working market, alive each afternoon with the calls of auctioneers and the bustle of buyers. The catch of the day – gleaming doradas, crimson gamba roja, and silver anchovies – is sold to wholesalers, restaurateurs, and curious locals who still gather to witness the ritual of the sea meeting the shore. And it even has its own fishmonger’s on one side of the building, selling fresh fish and seafood – at a premium, of course – between 4.00pm and 9.00pm Tuesday to Friday.

But the 21st century has brought new headwinds. Tourism-driven redevelopment and proposals to expand private moorings have stirred unease among the fishing community, raising questions about the balance between heritage and progress. Adding to these pressures are restrictive rulings from the European Union, which have drastically reduced the number of days the fleet is allowed to fish. These limitations threaten not only the viability of family-owned fishing enterprises and the steady supply of fresh local catch, but also the cultural identity of a town whose soul has long been tethered to the sea.

A little further around the harbour road sits the Club Náutico de Jávea, which has become an institution of the modern port. Founded in April 1958, it eventually established headquarters, secured a concession, and since 1988 has flown a Blue Flag for quality. Ambitious renovations followed in 2021, pairing investment with an extended concession that ties the club’s future to the harbour’s ongoing reinvention.

Ambitions to grow bigger have repeatedly collided with local will. A privately funded mega-marina proposed in 2014, Marina Punta del Este, inflamed residents and council alike by threatening Playa de la Grava’s openness; fierce opposition stopped the scheme, and a smaller canal marina, Marina Nou Fontana, opened in July 2017 instead.

Then the sea, relentless in its choreography, struck again: Borrasca Gloria in January 2020 was the latest in a line of great storms that ravaged the outer breakwater. Repairs meant placing vast stones near Restaurante Tangó, stones that would erase the tiny Cala del Popé. Debate raged: technical necessity or favouring private interests? The authorities argued the measures were the only feasible means to control scouring and protect the terrace; many locals still mourn a lost patch of shore, a piece of history where a Russian-Orthodox priest is said to have taken refuge in Xàbia after the Bolshevik revolution and used this small cove to bathe daily, even in winter.

Over the centuries, Xàbia’s harbour has grown from a modest Roman inlet into a busy port spanning more than 14 hectares. It now hosts fishing boats, a yacht club, and seasonal crowds drawn by tradition and tourism. The harbour remains central to local life, from the arrival of the Three Kings each January to the dramatic spectacle of Bous a la Mar in late summer. Though much has changed, traces of the past are still visible – the name of a high-rise that recalls the watchtower that once defended the coast, its old cannons now a place to rest outside the church in the old town,and the faint outline of a cove now buried beneath stone and concrete.

Caleta del Racó may be gone from the maps, but its curve still lingers in the harbour’s shape, a quiet reminder of where the sea once cradled the shore. It was never just a landing place, it was the beginning of Xàbia’s story. And though modern life moves quickly around it, the past is never far beneath the surface. Sometimes, all it takes is to slow down, open your eyes, and look closely. For the stones still speak. The shoreline still remembers.

Research Sources:

- xabia.org “El Port de Xàbia”

- xabiaaldia.com “1879 El año en que fue aprobaba la creación del puerto y el ensanche de Xàbia”

- cnjavea.net “Los inicios del Club Náutico de Jávea”

- yachtdigest.com “Puerto De Javea”

- restaurantepepeyestrella.es “Origenes e Historia del Puerto”

- restaurantepepeyestrella.es “El puerto de hoy”

- javea.com “El auge del comercio de la pasa en Xàbia”

- xabiaaldia.com “El talud del puerto de Xàbia antes de ser un talud”

- xabialdia.com “Las transformaciones y desaparición de la Caleta del Racó”

- javea.com “Refugios de la Guerra Civil Española en Xàbia”

- lamarina.eldiario.es “Xàbia, la de los jabalís y otras animaladas”

- javea.com “La Torre o Castillo de San Jorge”

- xabiaaldia.es “Los cañones de Xàbia”

- xabiaaldia.es “Xàbia, litoral de torres y castillos (I)”