In the long shadow of the Taifa of Dénia’s dramatic fall in 1244 – when betrayal and siege shattered one of the last Muslim strongholds on the Valencian coast – the fertile valley of Xàbia passed into new hands. Absorbed into the rising Kingdom of Valencia, its lands were granted to Christian lords, and settlers from Cataluña soon arrived to repopulate a countryside hollowed by conquest and exile.

Yet peace was fragile. From the south, Moorish raiders swept through the borderlands, while North African corsairs prowled the coast, plundering villages and dragging captives back across the sea to spend the rest of their miserable lives in slavery. Pressed by these constant dangers, the settlers built their community upon a gentle hill, a mere 1.5 kilometers inland from the coast, thought to have been located on the scant remains of an old Moorish hamlet that itself rested atop traces of a Bronze Age past.

Ever wary of the perils that haunted the coast, the new settlers anchored their lives around the high ground where the ancient church now rises. There, they built a fortified enclosure, thought to have consisted of thick rammed-earth walls braced by corner towers, born of fear and necessity, a fragile bulwark against the chaos beyond. Of those early defenses, nothing endures with certainty, save perhaps a low remnant of wall at the base of a modest tower, the Torre d’en Cairat, which faces the eastern end of the municipal market. Once likely part of a Moorish farmstead, it has long since been absorbed into a stately house, typical of Xàbia’s historic heart.

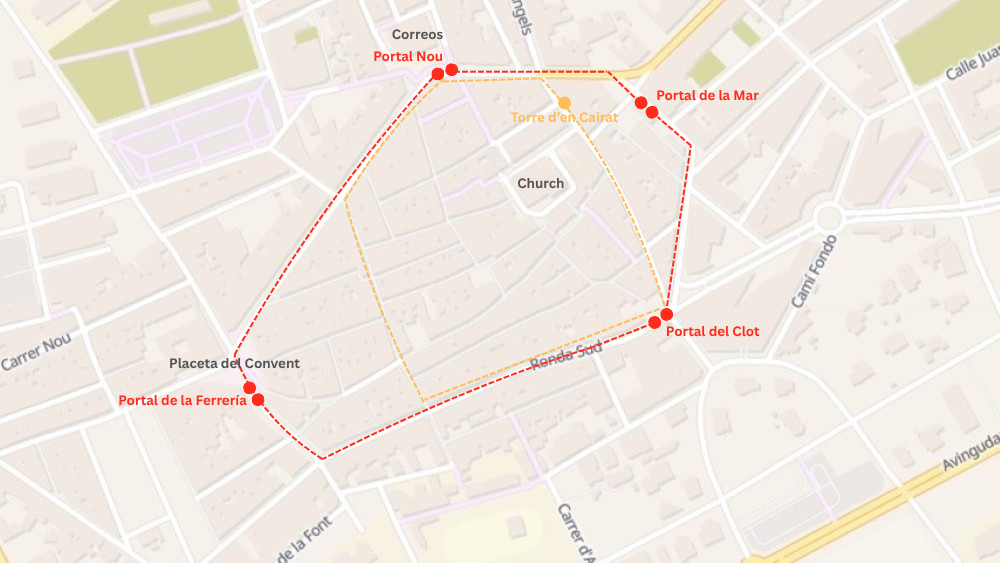

Archaeological excavations have sought to trace the footprint of this early fortified nucleus. Its boundaries likely stretched eastward to Carrer Roques, south to the Ronda Sur, west to the streets of Sant Josep, Verge del Pilar, and Pastors, and north to Avenida Príncipe de Astúrias and Ronda Nord, tracing the faint imprint of a community shaped by vigilance, survival, and the rhythms of a bygone era.

In 1301, Jaime II, king of Aragón and Valencia, ever mindful of the ceaseless danger that prowled his coasts, ordered the people of Dénia to retreat within the castle’s walls. At the same time, he forbade the inhabitants of Xàbia from continuing the defensive tower they had begun to build, seeking instead to concentrate the region’s strength in Dénia, the administrative and judicial heart upon which Xàbia depended.

But danger would not be contained by royal decree. In September 1304, six raiding ships from North Africa, joined by Moorish cavalry sweeping up from the south, descended upon the valley of Xàbia, burning and plundering as they came. In the face of this devastation, the king ordered the Xabieros to abandon their homes and take refuge in the fortress of Dénia. Yet even the king could see that his realm required a stronghold on the southern flank of the Montgó massif. In December 1304, he reversed his earlier command, instructing the people of Xàbia to halt the demolition of their tower and to rebuild it at once.

Still, progress was slow. By 1308, the tower remained unfinished, and the king’s patience wore thin. Frustrated, he issued a final warning: the Xabieros were to complete their tower without delay or face forced resettlement in Dénia, a threat which, it seems, did more to hasten the tower’s rise than any fear of corsairs ever could.

As Xàbia’s population expanded during the 15th and early 16th centuries, the original enclosure walls proved too confining for the growing town. As the urban footprint spread east and west of the ancient nucleus, a new perimeter was laid out, one still traced today by the ring road, giving the historic centre its characteristic angular shape.

The new defensive walls were formidable: over a metre thick in places, built with a dense mortar of lime and hard limestone, with tosca blocks reinforcing the angles and corners. Between the walls and the houses ran a narrow alley, just 2 to 2.5 metres wide, a buffer that added both security and discipline to the town’s layout.

Three principal gates pierced the walls: Portal del Clot to the south, leading to the fields; Portal de la Ferreria to the west, giving access to inland routes to other settlements; and Portal de la Mar to the east, giving access to the sea. In the early 19th century, a fourth gate, Portal Nou, was added to facilitate movement to the north. The gates – and the eastern wall in particular – were strengthened with round towers, some armed, and over the gateways, imposing machicolations projected, ready to repel any who might dare approach. Each evening the town’s routine folded into a ritual of control, bells and watchmen signalling closure, sentries pacing the walls and the church tower’s bell ringing should warning be needed.

From the 16th century onwards, the Barbary corsair’s shadow fell across the Valencian coast, and Xàbia’s architecture, customs and urban psychology were adjusted accordingly. Narrow, interlocking streets made pursuit and plunder harder for raiders; fortified homes and the protective presence of San Bartolomé offered refuge; and the gates, which were kept closed at night, turned the town into a hard nut along a soft coastline.

There is an old saying in Xàbia: “Smoke in the pine forest, Moors on the coast.” It recalls the days when watchtowers along the shoreline sent up plumes of warning smoke, signals that danger was near. At the first sign of threat, the town’s walls were inspected and hastily repaired, while livestock, women, and children were sent to take refuge within the fortified safety of Dénia, and the able-bodied men stood ready to defend their homes.

In May 1561, the Portal de la Mar, the gate nearest the sea, was walled up and sealed after reports arrived that a fleet of Barbary galleys had been sighted offshore. Eight years later, when word of the Morisco uprising in Granada reached Xàbia, the council once again ordered provisions to be gathered and every defence inspected, fearing that the Moriscos of the Marina Alta might also rise in rebellion. And, as late as 1812, a band of privateers landed on the coast, slipping through a breach in the ancient wall to plunder the grand houses of Xàbia’s wealthy, proof that even in more modern times, the sea could still bring danger to its door.

Yet walls that serve one century can become obstacles in the next. The raisin trade, which emerged as the town’s main economic engine in the early 19th century, was flourishing as new North American markets opened up, replacing the declining demand from England. Expansion plans and harbour works called for wider streets, easier cart access, and space for a growing population. Thus, during the 1860s and 1870s, large sections of the ancient walls were dismantled, their masonry no doubt reused in new buildings or reduced to rubble, while the old gates were torn down as town planners carved broad avenues where the defences had once stood. The argument was that the grand walls which had once offered protection now seemed more confining than secure. The village had begun to spill beyond its historic boundaries, giving rise to new suburbs and expanding districts that demanded better infrastructure. And so, by 1874, Xàbia’s defensive circle had all but disappeared.

The walls remained largely a memory for more than a century, eventually immortalised in a large model of the medieval town, now displayed in the municipal museum. Today, tosca stone crosses mark the locations of two of the four original gatehouses – Portal del Clot and Portal de la Mar – while the famous Nit dels Focs each June deliberately traces the route of the long-vanished walls, with four of the six fires that daring participants leap through positioned at the sites of the old gates.

In the early 21st century, supposed remains of a section of the town wall were uncovered beneath Avenida de Príncipe d’Asturias during a €20 million improvement project in the historic centre. The local council incorporated these remains into the modernisation works, yet the gesture failed to capture the imagination of some residents, particularly as it removed valuable parking spaces along the main street. Yet, these reconstructed fortification, built on the original foundations, give visitors a sense of the town’s medieval defences.

The decision to pull down the walls in the 19th century was seen at the time as a form of liberation, allowing Xàbia to embark on an ambitious expansion that shaped the town’s development in the latter half of the century. Local authorities prioritized growth and modernization over preservation, confident that progress required the removal of these centuries-old defences.

Almost 150 years later, however, the conversation has changed. Across Spain, other towns and cities have managed to retain their fortifications or at least significant sections of them. Popular destinations such as Ávila, Lugo, Cáceres, Morella, Peñíscola, Toledo, and Pamplona now protect and integrate their walls into urban life, viewing them as cultural and touristic assets rather than obstacles. One cannot help but wonder: how different would Xàbia’s historic centre be today if its walls – or even sections of them – had survived? How much might they have enhanced the town’s appeal to visitors, adding depth and character to its streets and squares?

Sources:

- Xàbia Tourism Portal, “Medieval and modern architecture”.

- Wikipedia, “Xàbia” (overview and archaeology notes).

- Xàbia Town Council event page, “The Village by night. Xàbia’s medieval secrets”.

- SpainLifestyle, “The architectural and spiritual growth of medieval Xàbia”.

- Javea.com, “History of Xàbia: When and how did the town begin to grow?”.

- The Xàbia Museum Project: Museum Panels