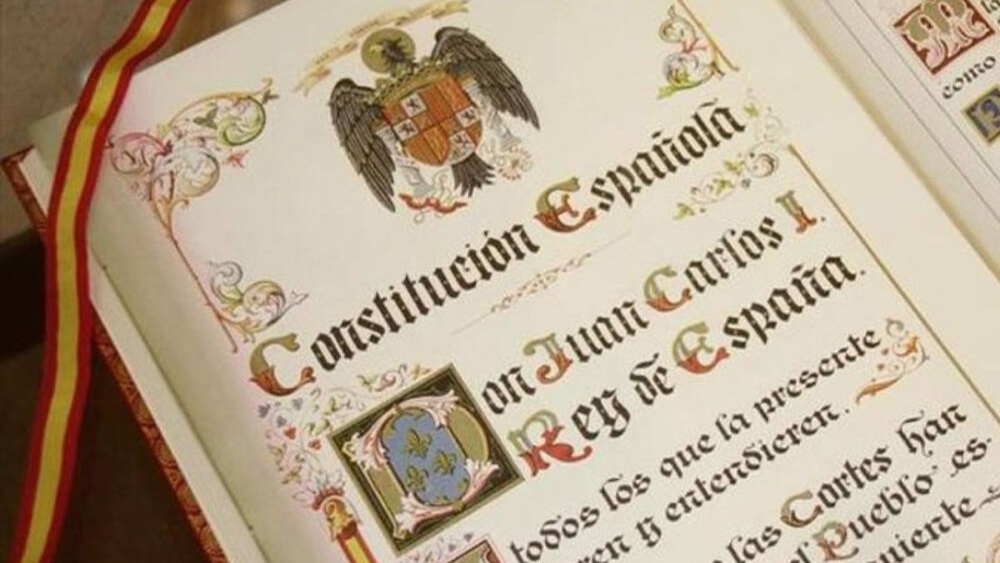

In December 1978, Spain took a decisive step into democracy. After nearly four decades under General Francisco Franco’s dictatorship, Spaniards voted overwhelmingly in favor of a new constitution, a document that would reshape the nation’s political, social, and cultural identity. This was not Spain’s first attempt at constitutional rule but its eighth constitution since the liberal charter of 1812. Yet unlike its predecessors, the Spanish Constitution of 1978 would prove enduring, marking the culmination of La Transición, a period of cautious reform, compromise, and hope that transformed Spain from an authoritarian regime into a modern constitutional monarchy.

The Context: La Transición

In 1969, Franco named Juan Carlos de Borbón as his official successor, believing that the young 31-year-old prince could be molded to continue his authoritarian legacy. At first, Juan Carlos, newly titled Prince of Spain, appeared loyal to the regime that had selected him. Yet as the dictator’s health declined, the prince began to meet secretly with opposition leaders and exiles, listening to those who longed for liberal reform and democratic renewal.

The final chapter of Franco’s dictatorship began on October 30th 1975, when the ailing general formally handed control of the government to the prince, just three weeks before his death. Upon Franco’s passing, Juan Carlos was proclaimed King of Spain on November 22nd 1975, and in his inaugural address, he spoke of three guiding principles for the nation’s future: historical tradition, national laws, and the will of the people.

Over the next two years, the king pursued a careful but determined path toward reform. In July 1976, he dismissed the conservative Prime Minister Carlos Arias Navarro, who had tried to preserve elements of the old order, and replaced him with Adolfo Suárez, a pragmatic reformer and former Francoist who understood that Spain’s survival depended on democratic change.

Suárez proved the ideal bridge between past and future. On December 15th 1976, under his leadership, Spaniards voted overwhelmingly – 94 percent in favour – to approve a law initiating the transition to parliamentary democracy. This referendum opened the door to the first free general election since 1936, held on June 15th 1977, which Suárez’s centrist Union of the Democratic Centre (UCD) won with 34.4 percent of the vote, five points ahead of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) led by Felipe González.

Just five months later, on October 25th 1977, the historic Moncloa Pacts were signed, a broad agreement among political parties, trade unions, and the government on how to stabilize Spain’s fragile economy and consolidate democratic institutions. These accords proved that Spain’s political forces could cooperate peacefully, setting the tone for the consensus that would define the drafting of the constitution.

Drafting the Constitution: The Fathers of Democracy

The new constitution was entrusted to a select committee of seven parliamentarians, later known as the “Fathers of the Constitution” (Padres de la Constitución). They represented a remarkable cross-section of Spain’s emerging democracy: centrists Gabriel Cisneros, Miguel Herrero y Rodríguez de Miñón, and José Pedro Pérez-Llorca; the socialist Gregorio Peces-Barba; the conservative Manuel Fraga Iribarne; the communist Jordi Solé Tura; and the Catalan nationalist Miquel Roca Junyent.

Together, they embodied the spirit of dialogue and compromise that defined La Transición. Their task was monumental: to produce a constitution capable of reconciling democrats and former Francoists, secularists and Catholics, centralists and regionalists.

After more than a year of debate and negotiation, the Spanish Government approved the new constitution on October 31st 1978. The document confirmed Castilian (Spanish) as the official language of the state while recognizing regional languages, such as Catalan and Valencian, as co-official within their respective autonomous communities. It also reaffirmed the design of the national flag, established that Madrid would remain the capital, and acknowledged the flags and symbols of Spain’s autonomous regions.

The constitution guaranteed ideological and religious freedom, personal liberty, and freedom of expression, enshrining for the first time in modern history the individual rights of all Spaniards under democratic law.

Key Principles of the 1978 Constitution

The Constitution established Spain as a parliamentary monarchy, with the King as head of state and an elected Parliament (Cortes Generales) as the legislative power.

Its key principles included popular sovereignty, the recognition of regional autonomy for historic nationalities such as Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Galicia, the separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, and the protection of civil rights and human dignity. Above all, it reflected a firm commitment to democracy and the rule of law, a delicate balance designed to prevent both authoritarian relapse and regional fragmentation.

The Referendum of 1978

On December 6th 1978, Spaniards were called to the polls in a national referendum to approve or reject the proposed constitution. The result was overwhelmingly positive: a 67.1 percent turnout, with 87.8 percent voting in favor and only 7.9 percent opposed.

Yet the “No” vote, though small, reflected lingering divisions. On the far left, some viewed the constitution as too cautious, a reform of Francoism rather than a clean break. The Basque nationalist party Herri Batasuna urged abstention, arguing that the constitution denied the Basque people’s right to self-determination. Meanwhile, Francoist loyalists on the far right opposed its regional concessions and the legalization of left-wing parties.

Despite such dissent, the result demonstrated a clear national consensus: Spaniards wanted democracy.

A Lasting Legacy

The Spanish Constitution of 1978 officially came into force on December 29th 1978, marking Spain’s full return to democratic rule. It has since provided stability through turbulent decades, surviving attempted coups, economic crises, and regional tensions.

Each year, Spain celebrates Constitution Day (Día de la Constitución) on December 6th, honouring the document that united the country’s future around democracy, pluralism, and the rule of law.

Commemorating the Architects of Democracy

Adolfo Suárez, the pragmatic reformer who guided Spain through its most delicate years, remains one of the most revered figures of La Transición. When he passed away in March 2014, tributes poured in from across the nation.

In June 2014, the local council in Xàbia voted unanimously to rename its central port square Plaza del Presidente Adolfo Suárez, a quiet yet fitting tribute to the man who helped bring democracy to Spain’s shores, both literally and symbolically.

Reform and the Future

Although the 1978 Constitution remains the cornerstone of modern Spain, debate continues about the need for reform. Issues such as the structure of regional autonomy, gender equality in royal succession, and the role of the Senate have prompted calls for modernization.

Only two amendments have been made so far: in 1992, allowing EU citizens to vote in local elections, and in 2011, introducing a balanced-budget requirement in line with EU fiscal policy.

Yet any significant change demands a broad political consensus, something as elusive today as it was in 1978.

From Dictatorship to Democracy

The Spanish Constitution of 1978 was more than a legal text; it was a national pact, a bridge between Spain’s authoritarian past and its democratic future. Forged through compromise, dialogue, and courage, it remains a testament to the belief that even the deepest divisions can be healed through understanding.

Click here to download a PDF file of the full Spanish Constitution in Spanish >>

Click here to download a PDF file of the full Spanish Constitution in English >>